By Mark Ellwood

Expect to mingle with the locals at Chem Chem Safari in Tanzania —even poolside.

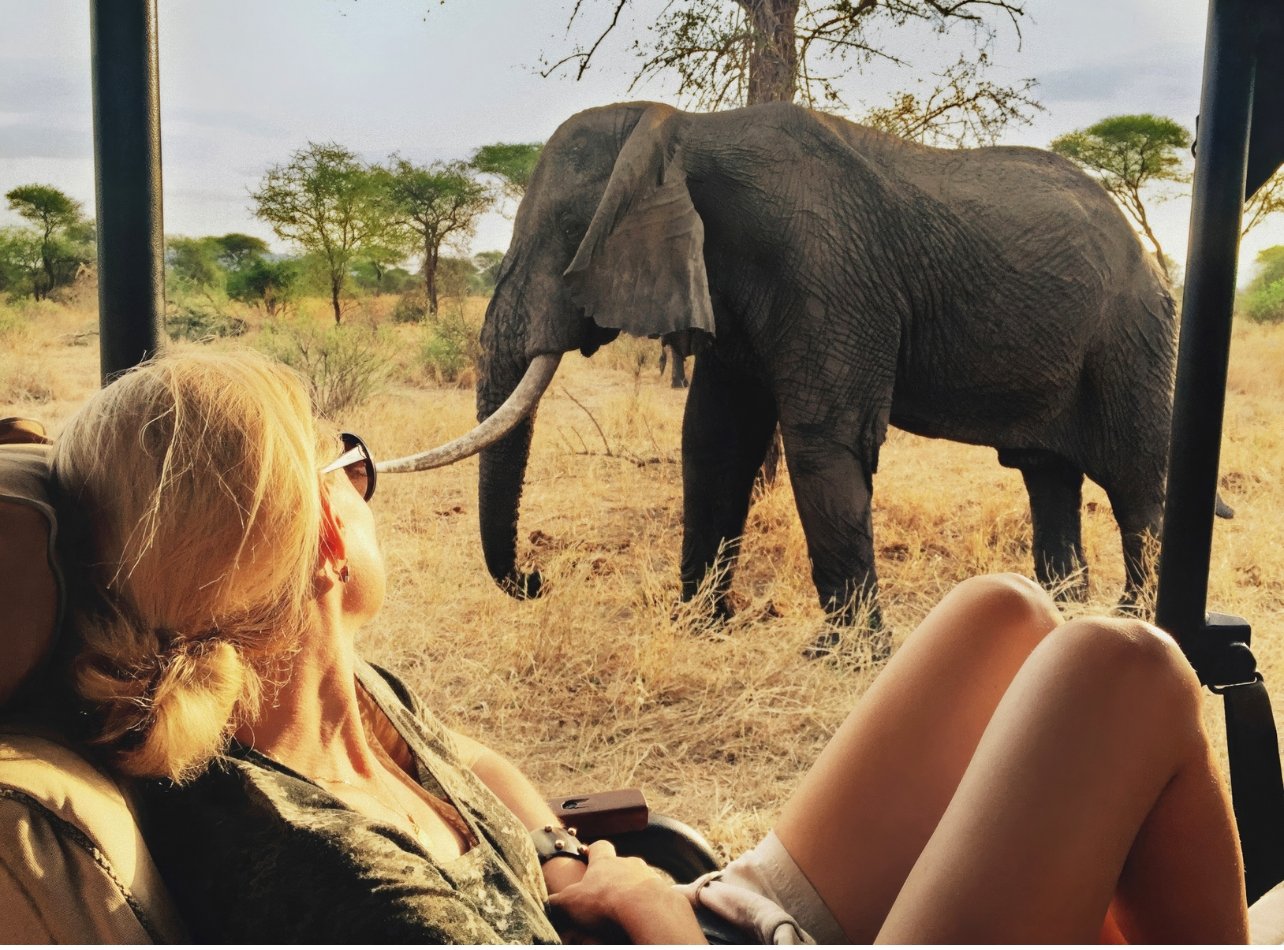

Chem Chem Safari founder Fabia Bausch relaxes close to a Big Tusker elephant.

Fabia Bausch was adamant about her concept for Chem Chem Safari in Tanzania: “It’s not a summer camp or a boarding school.” The Swiss investment banker’s first experience with safari in Africa had left her unimpressed: rigid schedules, forced socializing at meals, breakneck pace during the day, and intense pressure to engage with information at every moment. “It was not what I considered going on a journey of discovery in nature,” she recalls. So, Bausch resolved to fix what she considered the broken model, proudly focusing on what she dubbed slow safari. “People put so much negativity on the word slow. It doesn’t mean boring; it’s about being flexible, and doing things at your own pace.” Chem Chem—Swahili for spring—would allow its guests to approach the African bush at a quieter pace and so, she hoped, enjoy a higher caliber experience.

The first Chem Chem camp opened 13 years ago, when the slow approach was more novel. These days, though, focusing on quality rather than quantity regarding experiences has become a major force in travel. Slow Travel, of course, is a coinage inspired by the Slow Food movement, which originated in Italy in the 1980s and aimed to recapture the joy of savoring food and its surroundings. Slow Food was a backlash to the push for convenience at all costs that was then dominating the global food scene; Slow Travel is a reaction to the same problem in how travel experiences are marketed and packaged. It’s an emerging trend that challenges people to change the way they take trips, whether in pace, format, or a little bit of both. “There are lots of different strains of this,” explains Penny Watson, early Slow Travel pioneer and author of “Slow Travel: A Movement” (Hardie Grant Books, 2019). “It could be about taking a year’s sabbatical or a slow form of transport, or just a slow moment in a big city. It’s about being more thoughtful, more mindful about the cultures we come across. It’s about talking to the barista at the local coffee shop, or sitting down with someone there.”

Maasai guides lead Chem Chem Safari guests on bush walks, meditations, and runs near the lodge.

Bausch’s embrace of the concept is expressed in every aspect of her camp. At Chem Chem, safari isn’t limited to jeep drives: guests can run on the pans with a Maasai guard amid herds of giraffes and wildebeests, or take a silent walk for an hour to a fire circle, where they can write down something they wish to leave behind and burn it there, breaking the silence over a baobab tea infusion. Every guest has a private vehicle, and guide, ready to use as they wish: go out at 4 a.m. and stay the entire day in the bush with a picnic, or idle away the day at camp with a book and head out at 10 p.m. for a nighttime safari. “You’re welcome to do what you want,” says Bausch, “It’s your vacation—not mine.”

Pack it Up

Peruse our favorite travel bags, from duffels to carry-ons and more!

Explora Journeys, the new luxe cruise line, is one of the first among its rivals to embrace the idea of slow travel, too—in this case, quite literally. Captain Francesco Di Palma, vice president of itineraries management for Explora, explains that he plots voyages where ships can chug along at just 10 knots during sea days, versus the more typical 17 to 18 knots that is the average for cruise lines. “[Going slowly] allows people to really enjoy the open decks, and people can feel like they’re staying on a beautiful beach—at that speed, it doesn’t create much relative wind.” Di Palma is also responsible for scheduling, where the guiding values of slow travel are at the forefront, too. Traditional cruise itineraries pinball between places at breakneck speed, cramming in as many destinations as possible, perhaps with just six or seven hours in dock. Explora upends that idea entirely. He’s proud to say that ships will always remain in port for sunset, wherever they are, and not race away in mid-afternoon—others do so, Di Palma explains, to save on docking fees, while Explora believes that’s money well spent in enhancing passengers’ overall experiences.

Explora has reimagined how it spends time in port: often, ships will overnight at anchor in key destinations, from Monaco to Mykonos.

Explora has also reimagined how it spends time in port: often, ships will overnight at anchor in key destinations, whether Monaco, Venice, Dubrovnik, or Mykonos. This allows guests to better experience the local vibe and culture of a place after other daytrippers have departed: One in five of our passengers, Di Palma says, will go out for dinner or a drink that evening in town, unafraid of missing a departure time. Explora’s itineraries are deliberately modular, which allows this approach: travelers can sign up in batches of seven days on a single ship, and will see no repeated ports for three weeks. This encourages them to spend longer on board—a smart business decision, of course, but also one that recognizes that travelers now want to savor the experience rather than gulp it down.

Other companies are launching longer, slower itineraries expressly aimed at those able to disengage for three weeks or more. See the Sabbatical Buyout package for 30 days offered by Casa Chameleon Las Catalinas in Costa Rica, for example, which includes a dedicated assistant, private chef, car and ATV, plus one day per week dedicated to learning a new skill: sea fishing, perhaps, or cooking local dishes. The 34-day Great Indian Adventure from Wild Frontiers includes nights spent idling on the backwaters of Kerala on a private houseboat. The Swiss Alps-based Tschuggen Grand Hotel has its Moving Mountains program, expressly aimed at pushing guests to immerse themselves in the surrounding landscape; it includes foraging excursions in the forests for berries and mushrooms, or fishing in the mountain lakes.

A dramatic pool vista aboard Explora Journeys’ Explora 1.

The Italian region of Emilia-Romagna announced a Year of Slow Travel in 2019, aimed at encouraging tourists to explore its quieter corners, mostly relying on historic pilgrimage paths that were first established centuries ago by Holy Land–bound pilgrims. Routes include the 89-mile via Francigena, or the 40 miles or so of the via degli Dei before it crosses into Tuscany. Between 2021, when Covid-era border closures were lifted, and 2023, there was a 20-percent increase in usage, and four new paths have been added this year. Walk Japan specializes in small group walking tours, allowing guests to soak up the landscape around them, as on the Shio-no-Michi: Salt Road trip, which follows mountain trails and hikes that shadow one of Japan’s old overland trading routes in Nagano and Niigata Prefectures.

The Slow Travel concept is particularly well suited to Asia, at least according to Catherine Heald of ultraluxe specialist Remote Lands, which specializes in the area. “Japan can be so spiritual, and people want to take more mindful journeys. You don’t have to go to every temple in Kyoto, or every garden: go to a few and spend more time in them. You can’t see them all anyway—it’s impossible—so it’s better to do a smaller number really well.” In the pandemic’s wake, Heald has seen a transformation of her clients’ asks, with far fewer focused on what she calls “touch and go”: box-checking visits that barely scratch the surface. Now able to work remotely more readily, and keener to engage with the world for longer, clients now stay around 20 percent longer in cities like Tokyo, Seoul, or Bangkok than just five years ago. Heald wrangles experiences on Aman Private Jet Expeditions, too, and has adjusted guests’ overnights in the same way. Clients stay at least three nights in any place, rather than two, allowing them to feel less rushed and more relaxed. In Rajasthan, for example, that extra night unlocks the chance to go to Sariska National Park, perhaps, or rekindle a long lost yoga practice.

It’s an idea, and an ideal, that Penny Watson endorses wholeheartedly. The journalist and author is glad to see the rest of the industry catching up to the early principles of Slow Travel. “It used to be crazy what you would try and squeeze into a trip,” she says, “But now we’re far more aware that sitting around without ‘doing anything’ is good for us, too.”