Author and critic Ruth Reichl. Photo by Evan Sung.

By Andrew Friedman

When it comes to my relationship with chefs, I’ve got it pretty good. In 2000, my wife and I celebrated our wedding—an announced elopement—with an intimate lunch personally prepared by Alfred Portale at New York’s Gotham Bar and Grill, and a month later with a party at Union Pacific, where Rocco DiSpirito was a phenomenon. For my book “Knives at Dawn,” I was welcomed behind the scenes at the French Laundry, Thomas Keller’s landmark Napa Valley restaurant. And so on… It’s been 20 years now that I’ve been writing about the professional kitchen.

But I’ll tell you something: As a chronicler of chefs, I’ve got nothing on Ruth Reichl.

Reichl’s place in the food world isn’t news. It’s the stuff of legend and lore: Her life and career trace the evolution of new American cuisine, from her formative days in Berkeley, California, to her coverage of the Los Angeles restaurant scene of the late 1970s and 1980s, to her stints as The New York Times restaurant critic in the 1990s and then as editor of Gourmet magazine. Oh, and she has immortalized the double helix of her life and its culinary backdrop in a series of beloved, best-selling memoirs.

The riches of Reichl’s life render the privileges of mine positively paltry by comparison: How quaint that Rocco cooked for my wedding, when Ruth put him on the cover of Gourmet, the first chef ever featured there. Alfred treated us to lunch? Well, Ruth once helped Alfred cook at a benefit event she was covering. Those weeks observing at the French Laundry felt like a coup, but really what were they next to the fact that Reichl helped make the restaurant when she wrote in The New York Times, in 1997, that it was “the most exciting place to eat in the United States”?

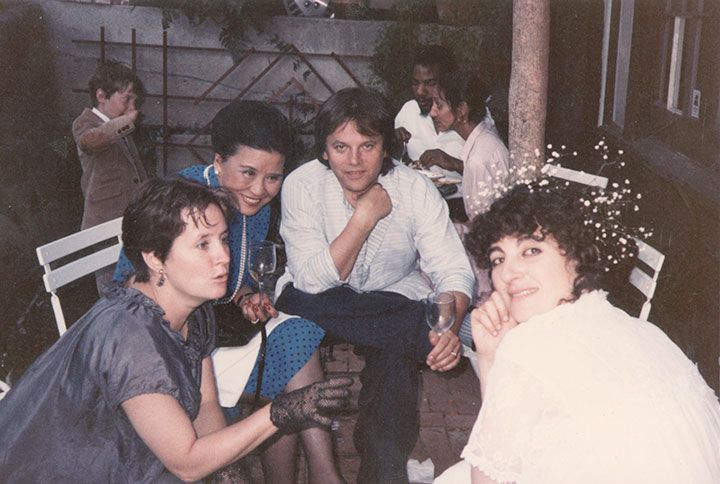

Chefs Alice Waters, Cecilia Chiang and Wolfgang Puck at Reichl’s wedding.

And yet, it wasn’t until I researched my book about the American chef movement of the 1970s and 1980s, “Chefs, Drugs, and Rock & Roll: How Food Lovers, Free Spirits, Misfits and Wanderers Created a New American Profession” (Ecco/HarperCollins), that I truly understood the chasm between Ruth’s life and mine, not merely the superiority of her titles and output, but of something greater and more uniquely hers. My book interviews conjured a moment of breathtaking innocence and access. Where today publicists, managers, agents and other gatekeepers control a chef’s time and often serve as consigliere during interviews, then there were no such go-betweens, and the result was reporting the rest of us can only dream of.

To learn more, I invited Reichl to lunch. She graciously accepted, and in December, we met on a sun-drenched weekday in the dining room of Porter House Bar and Grill, overlooking Central Park.

Reichl wears her prestige well. She arrived attired in emerald green that regally offset her trademark black bangs, and made my day by inclusively asking what I was working on. I kicked off our interview with a reality check: Was my impression, and envy, of her charmed professional life accurate, or the product of misplaced nostalgia? A smile spread across her face: “Oh, you are definitely right to be jealous.”

Over the next hour, she transported me with stories that left me as green as her ensemble, like the year she spent covering the genesis of Michael McCarty’s seminal restaurant Michael’s Santa Monica, becoming such a constant presence that at one point, McCarty, who’d run out of seed money, asked if she could loan him some.

“That’s how blurred the lines were,” said Reichl. “I spent so much time there that they forgot I was writing a story.” The moment exemplifies a defining dynamic of the era: Chefs and writers had more in common than not in those days, when the American food landscape was remade. “There was this sense that nobody cared about food, but we cared and we were promoting it together,” she said. A focal point was a new breed of professional cook—American, and often college-educated—who took cooking in more expressive directions. And so, Reichl, who had a masters in art history, covered chefs the way journalists covered other creative figures, introducing the public to the eclectic characters who were remaking American restaurants: Chez Panisse’s Alice Waters, McCarty, Michael’s chef Jonathan Waxman, Boston’s Lydia Shire, and on and on.

Chefs Alice Waters, Colman Andrews, Jonathan Waxman and Reichl.

“They were all fascinating to me,” she said. “It’s changed now: Chefs have become very self-conscious; in those days they weren’t. They were excited that you were interested in them… I just loved them.”

The food world of the time was minuscule. “There were a handful of us who really cared where American food went, and it was up to us to advance it any way we could,” she said.

The intimacy and shared mission made it perfectly natural for Reichl to ring up Waters and ask her to take her to Chino Farm, or to travel with chef friends to the opening of Mark Miller’s Southwestern restaurant Coyote Café in Santa Fe in 1987, or to spend a week on the road with Wolfgang Puck to write a Los Angeles Times profile. At one crucial moment, journalist and subject, seated alongside each other, nodded off on a flight. Puck snapped awake, sharing with her a nightmare that he forgot a catering gig for a Hollywood mogul. The moment gave Reichl the insightful ending to the story.

Reichl and Chef Jonathan Waxman.

“You can’t get those pieces if you have a PR person trailing along behind you,” she said.

Ironically, stories like that helped catapult chefs to a level of celebrity that threw down a roadblock for those of us who came later.

“Restaurants occupy a completely different place in the culture now,” she said. “It has to be the way it is now. It’s not a fledgling industry anymore. You need to recognize that reporters do one thing, critics do one thing, and chefs do another.”

That observation really brings home the most defining difference between Reichl and pretty much any writer of my generation: We may be lucky enough to write about a world we love as much as she, and even to probe its history. But Reichl is a part of that history—she helped forge the very world we inhabit—and it occurred to me as I put these thoughts down that for all of the heartfelt flattery I threw her way at lunch, I left out two crucial words: Thank you.

Leave a Comment