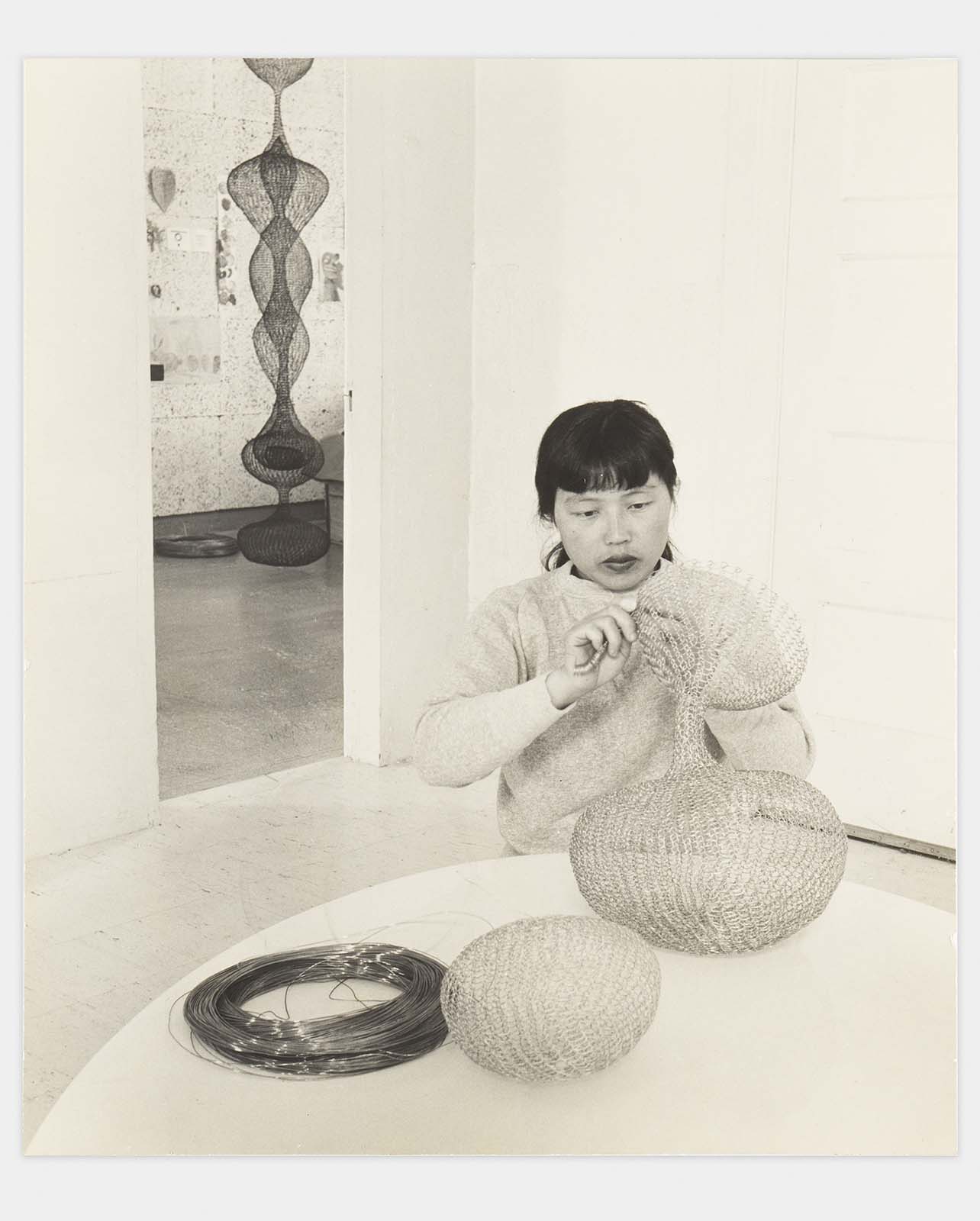

Ruth Asawa working in her home, 1956. Photo by Imogen Cunningham, © 2017 Imogen Cunningham Trust. Artwork © Estate of Ruth Asawa. Courtesy David Zwirner.

During the six decades of her career, the late American artist and outspoken arts advocate Ruth Asawa practiced a kind of alchemy, transforming everyday materials into spectacular works. Using the basket-making technique she learned in 1947 as a volunteer art teacher in Toluca, Mexico, she used her bare hands to weave wire into her most celebrated sculptures—sheer columns of voluminous, interlocking shapes that appear to float as they hang from the ceiling.

“For artists looking at Ruth Asawa today, she’s a model of making work that transcends category,” says San Francisco Museum of Modern Art curator Rachel Jans. The sculptor shaped wire in space to evoke pencil on paper, dissolving distinctions between sculpture and drawing. Meanwhile, her crochet-like process, which often left her hands nicked and cut, introduced so-called “craft” to the realm of fine art.

The mesmerizing contours and boundary-blurring techniques of Asawa’s wire sculptures, which are on view in “Lineage: Paul Klee and Ruth Asawa,” at SFMOMA and will be shown at David Zwirner gallery in New York this fall, are distinctly her own; they embody the singular inventiveness of an artist gifted with enormous vision and little means. Asawa was born in 1926, the eve of the Great Depression, in Norwalk, California, where her Japanese-born parents rented a small farm. Asawa and her six siblings grew up working in the field until the traumatic events of World War II, when 120,000 Japanese-Americans were forced into squalid internment camps. Asawa, then a teenager, spent 18 months of her life imprisoned.

“Sometimes good comes through adversity,” she said in 1994, reflecting on the silver lining of a nightmarish ordeal. “I would not be who I am today had it not been for the internment, and I like who I am.” In camp, Asawa took drawing classes from Japanese- American Disney animators. Later, she excelled at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College, a school made legend for cultivating artists like Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg, and challenging students’ resourcefulness with its notoriously low budget for art supplies.

“Rather than being concerned with your own design ideas and forcing your own ideas into it,” the artist explained in the 1977 documentary Ruth Asawa: Forms and Growth, Black Mountain’s esteemed faculty tasked her with critically examining cheap, ordinary materials for their own inherent qualities and potential. Under the close mentorship of Bauhaus painter Josef Albers and American architect Buckminster Fuller, she made her first wire sculptures in the late 1940s, already conditioned by hardship to value the beauty of the mundane: in scraps of wire, in the patterns of a leaf, or in myriad organic forms that would later emerge as defining features of her work.

Installation view of “Ruth Asawa: A Line Can Go Anywhere,” at David Zwirner London, 2020. Photography by Jack Hems. © The Estate of Ruth Asawa Courtesy. The Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner.

Asawa developed a wide-ranging, interdisciplinary practice of painting, drawing and cast sculpture, but her unparalleled wire works continue to be her best known. In 2020, they graced a commemorative edition of U.S. postage stamps, and in the same year, a single work from 1952 sold at auction for $5.4 million.

The artist, unfortunately, was not alive to witness either event; she passed away peacefully in San Francisco in 2013, shortly after opening her first solo exhibition in New York in 50 years.

“During her time, it was difficult for a woman artist using craft processes to be taken seriously,” Jans says, explaining why it wasn’t until the last decade that the art market recognized Asawa’s contributions: In the previous century, press had referred to her as a “housewife” rather than an artist, and saw her process as knitting rather than sculpture.

Because of her late commercial recognition, the prevailing notion is that success eluded Asawa until much later in life. The truth is, however, that she led a robust, active career after moving to San Francisco in 1949, raising six children as she continued to make work. Her lasting impact remains plainly visible, not only in every young artist successfully working with craft techniques today, but in the arena of public life. From the 1960s onward, she installed public sculptures throughout Northern California—fountains, a mosaic and bas-relief sculptures—while diligently promoting arts education through lobbying and advocacy.

Intent to pass the life-changing mentorship she experienced at Black Mountain College to the next generation, Asawa worked steadfastly to establish San Francisco’s first public school for the arts, which opened in 1982 and in 2010 was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts. (Never one to have idle hands, for years she maintained the school garden with student and parent volunteers.)

For a visionary practicing ahead of her time, art was not a career for Asawa, but the axis around which life humbly revolved. “I’m really concerned with how much I can pack into a day,” she said in the 1977 documentary, as the camera followed her watering and sketching the vegetables in her garden; teaching children about ink transfers; planning a sculpture for the Oakland Museum. Regardless of art world fame and fortune, art permeated even the most quotidian tasks. And, she said, “I really enjoy everything that I do.”

Eleanor Lahn March 08, 2022 at 12:19 pm

RE “…which are on view in “Lineage: Paul Klee and Ruth Asawa,” at SFMOMA and will be shown at David Zwirner gallery in New York this fall,” The exhibition was on view at SFMOMA July 10–December 5, 2021, according to its website, and I could not find it listed on the David Zwirner Gallery website.

Mary Cases March 08, 2022 at 10:49 pm

Absolutely gorgeous! I will spread the word. What a talent.

How wonderful to be featured in Bal Harbour Shops.

Mary Cases

Cases Realty Group, President

Licensed Real Estate Broker

3201 NE 183 Street, Suite 1204

Aventura, FL 33160

305-343-9689

sonia March 10, 2022 at 2:38 pm

Hi! where can I see her work?