From Assouline’s special edition, Formula 1: The Impossible Collection, photographer Darren Heath captures a pit stop during Lewis Hamilton’s second Formula 1 race at the 2007 Malaysian Grand Prix

Assouline’s Formula 1: The Impossible collection, available at Assouline Bal Harbour Shops

When plans were first announced about four years ago for the 2022 Formula 1 Miami Grand Prix, the first F1 auto race to be held in the city, it caused a stir. “I believe Miami is the most dynamic city in the country right now,” said Miami Dolphins CEO Tom Garfinkel, in an interview last year. The football team’s Hard Rock Stadium serves as the centerpiece for the race. “We try to bring things out here that reflect that.”

F1 racing is, after all, considered the world’s most popular form of motorsport, with an average of 24 million viewers tuning into a race. And F1’s Monaco Grand Prix is considered, along with the Indianapolis 500 and the 24-hour endurance race at Le Mans, a part of sports car racing’s Triple Crown. But big-time sports car racing is hardly new to Miami.

Sports car racing actually took place here as early as 1926, in what was then called “Fulford-by-the-Sea” (later to become North Miami Beach). Promoted by Miami Beach founder Carl Fisher, the course was constructed of wooden planks laid on an oval track, with 50-degree banked turns that required drivers to maintain speeds of 120 miles per hour, or risk sliding down into the infield. Alas, only one race was ever held on the track, which was destroyed, along with almost everything else in the area, seven months later by the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926. However, that one race drew 20,000 spectators to a venue designed to accommodate 12,000 and has been generally credited with laying the groundwork for the big-time racing dynasties now established in Sebring and Daytona.

It wasn’t until 1983 that Miami once again became a major auto-racing player. The single-seater sports car event known as The Grand Prix of Miami was the brainchild of Cuban-born Operation Peter Pan refugee Ralph Sanchez. It debuted on the streets of downtown Miami, along a 1.85-mile track that began in Maurice A. Ferré Park, then known as Bicentennial Park—where the Kaseya Center now sits—and extended for a stretch out onto Biscayne Boulevard. Though a torrential thunderstorm halted the initial running with only 27 laps completed, Sanchez stepped forward to pay the entire $1 million-plus purse. “As a young boy, my father loved the very concept of the Cuban Grand Prix,” says Sanchez’s daughter Patricia. “He loved racing, and he came to love Miami. The idea of bringing the attention of the whole world to this city was his way of giving something back. He wanted to turn Miami into Monaco.” As for her father’s insistence that the full prize money be paid, she was not surprised.

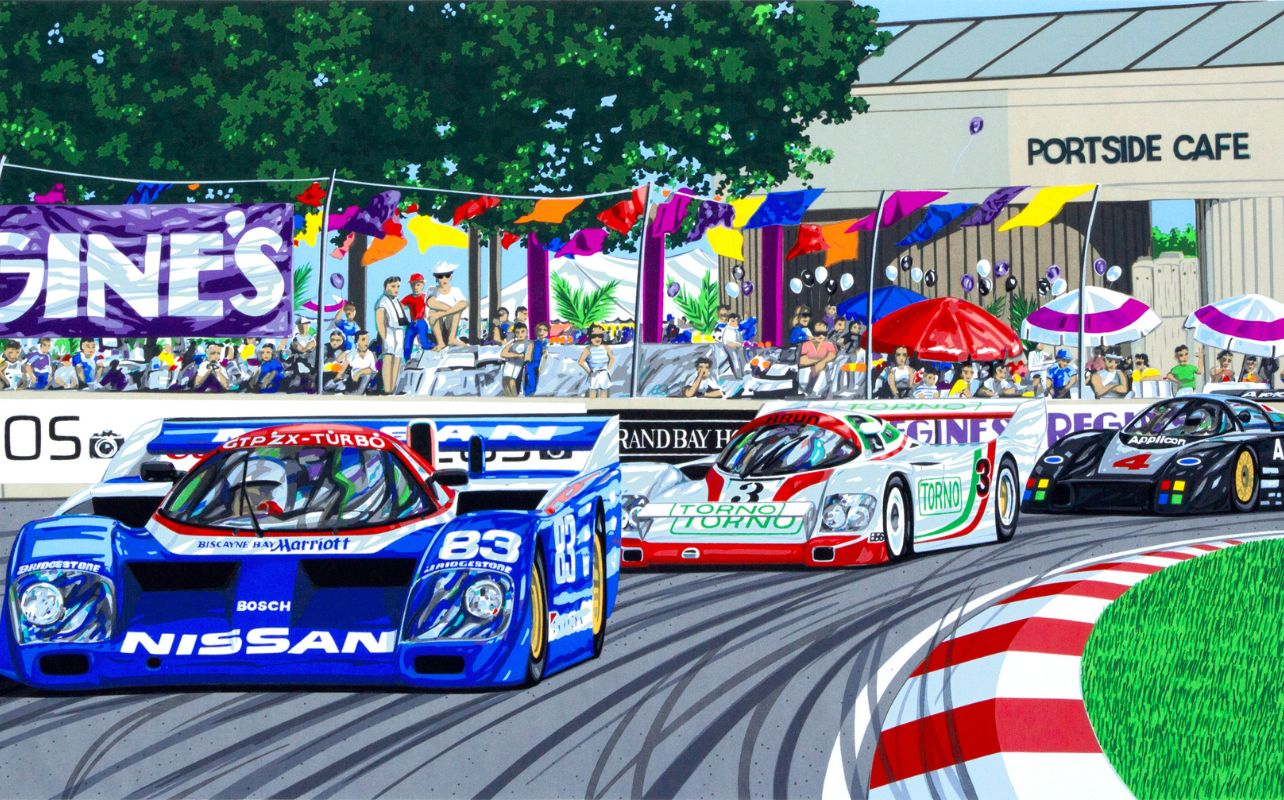

Randy Owens created the commemorative poster for the 1987 Grand Prix of Miami

“Financially, it was devastating, but it was never about the money. And his doing that was a defining moment. It transformed him in people’s eyes from just another guy trying to promote an event into a respected professional.”

The next year, Sanchez convinced former world racing champion Emerson Fittipaldi of Brazil to come out of retirement and take part in the Miami race. Fittipaldi didn’t win, but his interest in racing was rekindled—he would go on to win the Indianapolis 500 in 1989 and 1993. The Grand Prix of Miami continued in various iterations until 1995, when the track was demolished to make way for what was then called American Airlines Arena. Sanchez would go on to build the Homestead-Miami Speedway, which has become a mainstay on today’s NASCAR circuit. In many ways, that early Grand Prix of Miami probably embodied much of what present-day organizers hope the F1 Miami Grand Prix will become. Though the 2022 event was also proposed for the downtown streets, residents complained about the prospect of noise and traffic disruption, so the venue was switched to the grounds of Hard Rock stadium and neighboring Miami Gardens.

Last spring, as many as 1,000 laborers were deployed to build and create what organizers promised would be “the quintessential Miami experience.” There were 85,000 temporary bleacher seats in grand- stands distributed around a nearly 3.33-mile track, with a faux marina including model “yachts” installed at the seventh turn. A later turn featured a landlocked beach.

The original Grand Prix of Miami may have faced resistance from the city fathers, but not nearly what F1 organizers confronted in 2018. As one Sanchez confidante points out, “You have to remember that downtown Miami was not nearly so well appointed or congested as it is today. There were few hotels and restaurants, no Arena, no Bayside Marketplace, no Arsht Center, no Frost Science Museum, no Pérez Museum, and only a handful of condo dwellers.”

Sanchez also had the backing of Miami heavyweight developer Sherwood “Woody” Weiser, whose five-star Grand Bay Hotel in Coconut Grove served as the chief lodging and watering spot for celebrities, including Michael Jackson, Elizabeth Taylor, Sophia Loren, and untold legions of “cocaine cowboy” hangers-on during the Miami Vice 1980s. Eventually, the race was approved.

“We created the Regine’s Grand Bay VIP Club inside Reflections restaurant [where Bayside Marketplace now stands],” says one of the event’s organizers. “Tickets for gourmet dining, top-shelf liquor, and an unbeatable view of the race, the bay, and the downtown skyline, went for $500.” That was no small sum in 1983, but by comparison, tickets for the VIP experience at the 2022 F1 Miami Grand Prix went for as much as $29,000.

The Miami International Autodrome at Hard Rock Stadium

When Reflections was razed to make way for Bayside Marketplace, longtime South Florida restaurateur Gene Singletary oversaw the relocation of the VIP lounge to tented quarters in Bicentennial Park, near where the Pérez Art Museum Miami stands today. “Moving the VIP lounge to the grounds of the park meant that once the race started, VIP spectators were essentially trapped,” he says. “You couldn’t just go strolling across a track where cars were going 200 miles per hour. The only way in or out was by tug- boat shuttle between the old Flagler docks and the Port of Miami.” In the end, Singletary says, this element only added to the event’s unique character.

Noted racing world artist Randy Owens agrees. Owens, who created posters and other artwork featuring the original Grand Prix of Miami, thinks of the event in the same terms as the well-known races held in Long Beach and Monaco. “Monaco somehow made way for a race in the midst of the most valuable real estate in the world. And Long Beach and Miami ended up with revitalized downtowns after the races showed off their beauty.”

Those early races were unquestionably unique. Driver Danny Sullivan, who had won the Indianapolis 500 in 1985, came to the Miami race in 1986, and found himself approached by director Michael Mann, a fellow resident of Aspen. Mann cast Sullivan in an episode of Miami Vice, the plot featuring a race car driver accused of murdering a prostitute, with some scenes shot in the pit lanes of the Grand Prix of Miami.

“The Miami Grand Prix was a happening, and Miami Vice wasn’t just some TV show,” says Sullivan. “I remember on one of our breaks on set, I took [Miami Vice star] Don Johnson for a ride at speed,” says Sullivan. “He was yelling the whole time, but it was too noisy for me to hear what he was saying. When we got back into the pits, his hands were shaking so bad we had to help him take his helmet off—but he had a great time.”

Fast forward a few decades to last year’s inaugural Formula 1 Miami Grand Prix. The event, taking place on a typical May South Florida Day where temperatures hovered in the low 90s, was an instant sellout—even with general admission tickets beginning at around $600. The winner was Max Verstappen, a Dutch Red Bull Racing team member, who beat out Ferrari team driver and series points leader Charles Leclerc of Monaco. But by most accounts, it was the event itself that emerged triumphant, with the crowds exuberant and the drivers describing the track as looking like it had been there forever.

Maybe it’s because a bit of that original Miami Vice spirit lingers on.