By Kat Herriman

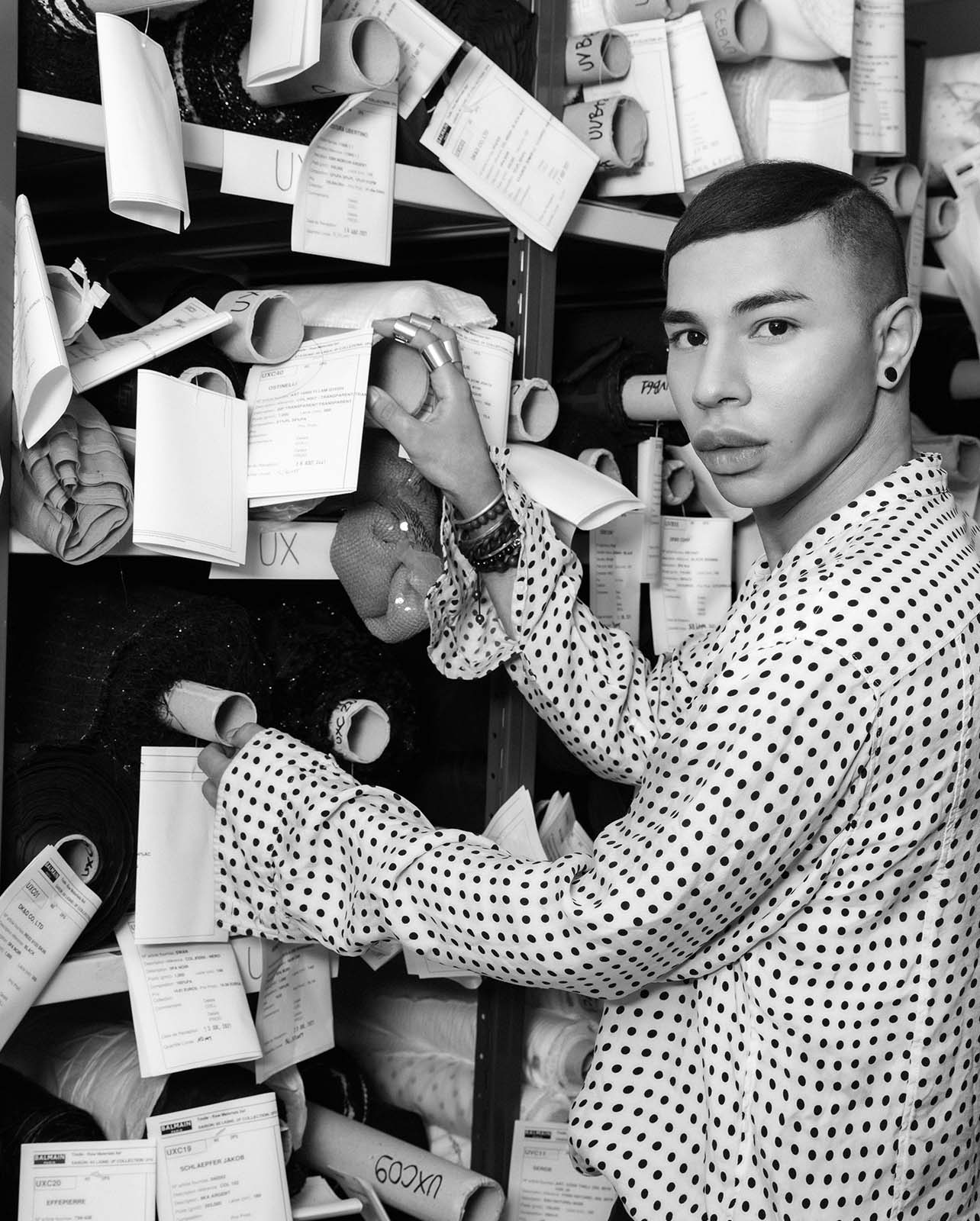

Olivier Rousteing in his Paris design studio; photo by Francesca Beltran.

A look from Balmain’s Spring 2022 collection.

I first encountered the magnetism of Olivier Rousteing while working at W magazine. The first Black designer to head a major French fashion house, Balmain’s Rousteing was seemingly born a press darling. Yet, celebrations collided with put downs: there was something about those first years of coverage across just about every glossy title that felt less like support and more like tokenism. W’s 2014 profile of the designer, titled “Phresh Out the Runway,” starred Rihanna, Iman and Naomi Campbell in Rousteing’s chunky bamboo earrings, beaded chokers and matching knitted dresses with abacus rows. The images captured by photographer Emma Summerton struck me as tone deaf, which I pointed out to my bosses. They told me no one would care.

They were right. There was no online fuss, just crickets. Now, that would never happen. Not because we have the @DietPrada police but because pioneers like Rousteing followed their own instincts for what Balmain should look like rather than caving to fashion’s worst.

Named creative director at 25, Rousteing spent his late twenties ignoring calls to tone down and scale back his active social media feed and celebrity ties, especially to the music industry. Today, Rousteing’s early muses, Rihanna and Kim Kardashian to name two, are unequivocally the most important fashion icons of our time. Not to mention the ubiquity of social media as a tool for fashion brands low and high.

In 2021, Rousteing’s prescient vision for the future feels almost psychic, yet it also reveals the depths of the industry’s elitism and narrow mindedness. “I’m really proud when I go to see fashion schools now because I can be the example. When I was younger, I didn’t have that example,” Rousteing explains. “But as a designer, you cannot be ashamed of the music you listen to and the icons of your time, you have to embrace them in your work. Not everyone needs to be influenced by the same mood board of the 60s and 70s and girls like Brigitte Bardot and Jane Birkin. I fight against that because I care about the future. I care about the new generation. I don’t want them to suffer from the same frustrations.”

I tell Rousteing over the phone that the W profile was one of the most memorable things I worked on; the imagery I understood at the time was immediate canon. It registered like Elizabeth Taylor’s jewels at Sotheby’s. I told him I knew I was in the presence of instant iconography, a witness of my generation.

In a recent podcast interview with Tim Blanks for Business of Fashion looking back on his past decade at the brand, Rousteing spoke about his original goal to make Balmain a household name. He explains that his signature social media vulnerability and celebrity collaborations with friends were not a liability, but rather the formula Rousteing used to raise the label to international prominence. Now, Balmain is a part of the pop vernacular—appearing in film and music as a luxury reference. “When I started at Balmain 10 years ago, many people didn’t know the name Balmain,” Rousteing explains. “Now my 11-year-old cousin knows—even without our relation. If you listen to music, Balmain is in the air.”

Rousteing at the finale of Balmain’s Spring 2022 show, with models including Naomi Campbell, Carla Bruni and Adut Ekach.

Last September, Rousteing celebrated the leaps and bounds he’s taken within the brand with the SS22 collection—a two-day festival punctuated with musical acts from the likes of Doja Cat and Franz Ferdinand, as well as runway cast including Naomi Campbell, Carla Bruni, Precious Lee and Alva Claire. The collection took a retrospective approach looking back at some of the standout garments the designer has put out. Examining one’s history is a new luxury that Rousteing has been reveling in. After six or seven years at the helm, he tells me that he began to feel free to explore emotional content that wasn’t solely protective. As a result, his armor-like silhouettes have softened with time, creating a sense of nuance that was not detectable in the first years. We saw this concept begin to reveal itself in the Fall 2021 collection, which starred Charlotte Stockdale and Katie Lyall as flight attendants, which blurred the rough edges of his embellished utilitarianism with candy-colored knits and padding.

“I started Balmain by almost being a warrior or, you know, a fighter,” Rousteing says. “I think it’s time that people knew this is a brand that started in 1945 and I’m just one chapter of it.”