Bittman in the Tuscan kitchen of his friend Olga, who taught him how to make “the best vegetable soup ever.” We have the recipe at the end of this interview. Photo by Lorenzo Pesce/Contrasto/Redux.

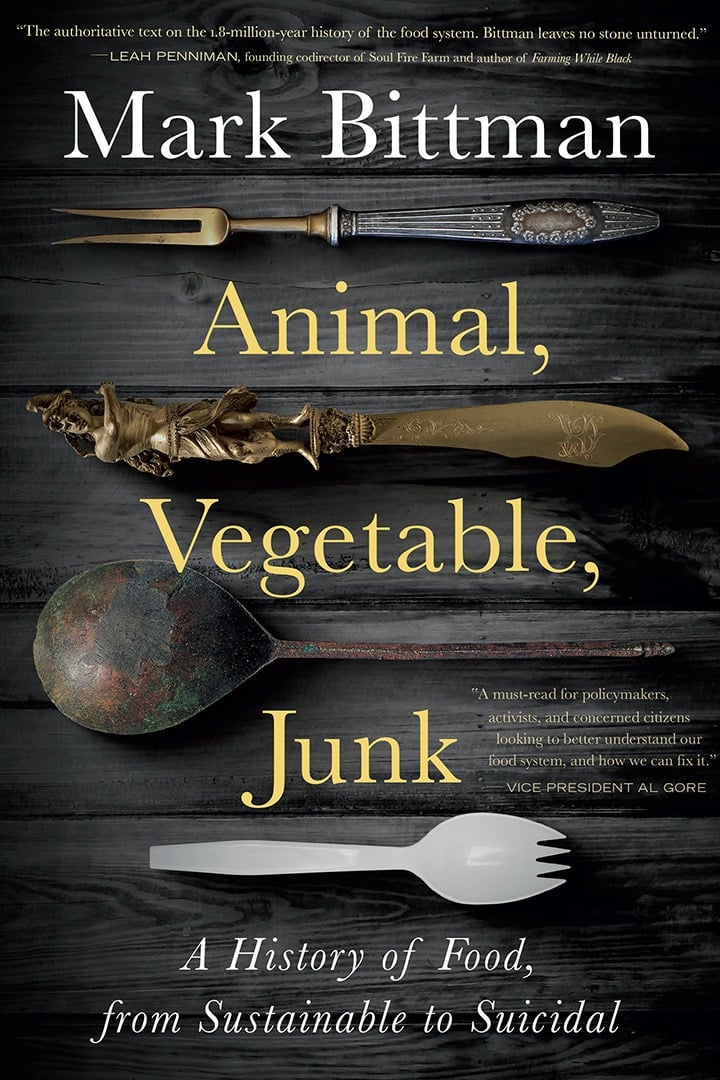

A beloved and bestselling cookbook author and food journalist, known to many as “The Minimalist,” Mark Bittman pivoted from instructing the mechanics of a recipe to shining light on the mechanisms that underlie food production. That Bittman is Special Advisor on Food Policy within Columbia’s School of Public Health—where he teaches and hosts the lecture series “Food, Public Health, and Social Justice”—is consistent with this recent chapter. He might be someone we’ve invited into our kitchens via his award-winning articles and books, but in Animal, Vegetable, Junk he’s found his fight. This book is not only urgent, it’s illuminating and instructive; and, for all of us who have admired Bittman’s writing over his long career, it is a pleasure to be guided by his pragmatic, compassionate voice.

Fanny Singer: Mark, the last time I saw you was at my mother’s restaurant, Chez Panisse, when you were living in California. Is that when you started working on Animal, Vegetable, Junk?

Mark: I did start the book when I was out there. Just being there got me thinking about it.

FS: It’s such an exhaustive, vast, admittedly somewhat harrowing, but also slightly hopeful tome.

MB: Slightly hopeful.

FS: To have the history of humankind re-contextualized around food was compelling, especially inasmuch as it creates a framework for understanding how we’ve ended up in an industrialized system on the brink of climate collapse. What made you want to write this book?

Mark Bittman’s newest release, Animal, Vegetable, Junk: A History of Food, from Sustainable to Suicidal. Available at Books & Books, Bal Harbour.

MB: When I was writing the Opinion column for The New York Times, between 2010 to 2015, it was hard to be nibbling at the edges of every one of these stories and never really going into the history except briefly. The columns were only 1,000 words. But I wanted to tell this as a unified story because people don’t credit food as the driver of history that it is. Ultimately, I don’t know whether it’s a success story or a sad story. We’ve gotten to the point where the Earth can support all of these people, which you could argue is a success story, though imperfect obviously. But there’s also a way in which it’s horrifying, as food is responsible for everything from gender inequality, to slavery, to climate change, etc. If there were justice we would have food security because there is enough food.

FS: That’s a highly qualified statement!

MB: It took us a lot of mistakes to get here. But now we know how to do it so the struggle is not “How do we produce enough food?” but, “How do we do that with justice?” Then it becomes a non-food question. It becomes a question of how we want to organize society, around food and everything else. There were several inspirations for this book, but among them was Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything, where she writes that if you want to address climate change you have to fix society, and only by fixing society can you address climate change. I think it’s equally true for food and climate.

FS: A principal takeaway was that innovation and capitalism are the enemies of sustainability, and by “sustainability” I mean the survival of our species. You explore human motivations in your book but it’s still tempting to ask the question “Why?” Why are we so hell-bent on achieving progress at the cost of our future?

MB: I think instead of progress, the question is growth. Why is big growth so important? But, I’m a little more optimistic than I was when I finished the book. That’s because you can call things progress or you can call things mistakes—it almost doesn’t matter. This is where we are. 10,000 years ago, humans started agriculture, and 600 years ago, Europeans started conquering the world, and 150 years ago, it was thought that industrializing everything was the way to go. Now, we can see clearly where the problems and challenges lie. If we organize society in the right way, we can save ourselves. We can feed ourselves. We can stop taking more out of the planet than we put back in. We can compensate for climate change even. I don’t think you could’ve said that fifty, even ten, years ago.

10 Dishes to Shake Up Your Routine recipes: www.markbittman.com/recipes.

FS: Can we actually get there given our deeply divided country?

MB: Little by little, you convince the people who are the most convincible then worry about the rest. I don’t think we have a choice but to work towards that. Those of us who recognize it have to talk about it. It’s a pipe dream to say the status quo can maintain because it can’t. We know that change is inevitable. If you want to talk about better agriculture, you need to talk about land reform and about getting land into the hands of people who want to farm it and grow good food. You need to talk about good food purchasing programs where the food we buy is local and organic and produced by workers who are treated fairly.

FS: Your discussion of what governments are able to do on a localized level was encouraging—it feels very hard as an individual to affect substantive change. Take for instance, the case study you give of Belo Horizonte.

MB: What happened in Brazil was that a local, grassroots initiative in the country’s sixth largest city went national: a commitment to buying from small, local farms; encouraging the growth of organic food and farm-to-school production; farm-to-table, institutional restaurants with a sliding scale so that anyone could eat affordably. A right to affordable, nutritious food became national policy, which is not the case in the US.

FS: You also talk about several inspiring domestic programs: the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, for instance.

Pasta Primavera, 8 Ways recipes: www.markbittman.com/recipes.

MB: Detroit was one of the first places I visited when I started writing the Opinion column. Ten years later, it was the last place I visited for the book. The biggest change I saw was how powerful the urban farming movement had become. At first it was a little under the radar, but now there are urban farms everywhere. Urban farming is not the answer to all our problems, but it moves things in the right direction. As Will Allen explained to me, it’s not only about farming, it’s about community organizing, showing the strength of people working together and showing people how food is really grown. The majority of people don’t know where food comes from!

FS: I’d love for you to speak to the difference between “sustainable” and “ecological.”

MB: Every word used by progressive farmers and cooks has been co-opted. The epitome was an ad I saw when I was watching football for “Michelob Organic Hard Seltzer.” I thought “Okay, that’s the last straw!” People have fought so hard for the word “organic” to have meaning and credibility, and now there’s Michelob Organic Hard Seltzer! But that’s one of the reasons I favor the word “agroecology.” First of all, it’s hard to co-opt because it’s such a terrible word. But really it means a blend of agriculture and ecology, and is especially meaningful if you remember that ecology is the study of the oneness of nature, the oneness of things on this planet.

5 Hearty Vegan Dinner recipes: www.markbittman.com/recipes.

FS: You bring to light several lesser-known figures. I knew about Civil Rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer and her “pig and a garden” initiative, but I didn’t know much about, say, George Washington Carver or Timothy Pigford, the people of color in this country who contributed to agriculture and science but were generally under-acknowledged. How did these people enter the narrative?

MB: Their stories jumped out to me. Among the most important were those of formerly enslaved people; enslaved people built a great deal of the wealth of this country and got very little to show for it. It was important to support and to highlight those stories—the same is true for women. And it’s important to notice that leadership naturally came from those people. Even now, if we’re going to have a sound future of food it’s not because wealthy landowners decide it would be better for all of us. It’s because people who are not in power organize and insist we do things differently.

FS: It comes from people who have been historically disenfranchised, not just people of color or women, but also the small farmers in this country who, since the beginning of the arc of the history you trace, have been oppressed by subsidies, growth mandates and industrialization.

MB: That’s a really good point, and I think something that came out in the course of writing the book. We have this vision of America as a nation of farmers. It’s true that there were always a lot of farmers in this country, but they were being done an injustice from the beginning. There was never the kind of support for small farming that we’ve been lead to believe. Many of us think “Oh, in the ‘80s small family farms really started to die.” Well yeah, that’s true, but it was the 1880s.

10 Fast, Easy, Satisfying Spring Salads recipes: www.markbittman.com/recipes.

FS: Before we sign off, I need to hear a brief invective against the concept of “superfoods.”

MB: Well, there’s no such thing!

FS: I love the moment in the book when you say, to paraphrase, “Potatoes are a superfood, goddamn it!”

MB: That stuff about the potato was interesting right? It changed civilization. It’s so nutritious that populations doubled when they adopted potato eating. Incredible. You can’t say that about blueberries.

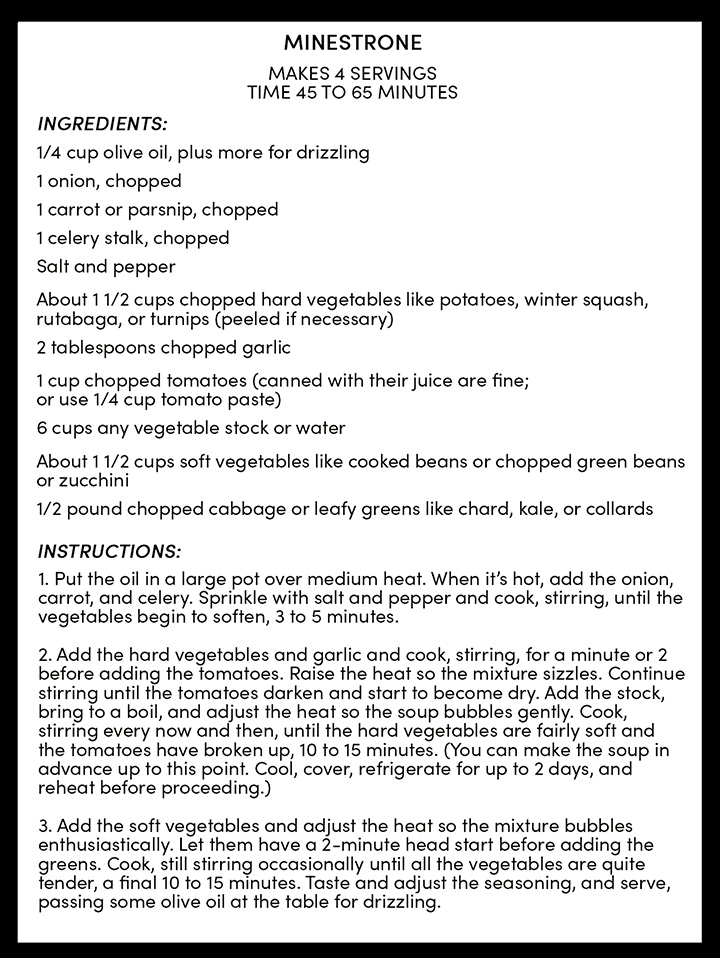

MARK BITTMAN’S FAVORITE MINESTRONE RECIPE

Minestrone, adapted from How to Cook Everything Vegetarian, 2nd Edition.

I’ve probably made minestrone once a month for years, never the same way twice. Tomatoes of some kind—fresh, canned, or paste—are the only constant; everything else is up for grabs. To facilitate this use-what-you-have approach, the ingredient list groups the vegetable options as “hard” and “soft” and gives a few suggestions, but soon you’ll be making this without a recipe. Trust me.

Leave a Comment